Unwired Planet v Huawei: UK High Court determines FRAND licence rate

05.04.2017

Mr Justice Birss has just handed down the first decision by a UK court on the ever controversial topic of what constitutes a FRAND royalty rate. At well over 150 pages, the judgment covers a lot of ground: a lot of ink is likely to be spilled about it over the coming weeks and months. From what we’ve seen so far, the judge has not been afraid to make findings that will have a considerable impact on licensing negotiations in the TMT sector.

We’ve summarised the headline conclusions below, but also keep an eye out for future posts in which we’ll analyse some of the judge’s findings and reasoning in more detail.

Background

In March 2014, Unwired Planet (“UP”) sued Huawei, Samsung and Google for the infringement of 6 of its UK patents. Five of these were standard essential patents (“SEPs”) that UP had acquired from Ericsson. They related to various telecommunications standards (2G GSM, 3G UMTS, and 4G LTE) for mobile phone technology.

Five technical trials, numbered A-E, were listed on the validity and infringement of the patents at issue. These were to be followed by a non-technical trial on competition law and FRAND issues. UP’s patents were found valid and infringed in both trial A and trial C, but two were held invalid for obviousness in trial B. Trials D and E were then stayed, and as Google and Samsung had settled with UP during the proceedings, this just left Huawei and UP involved in the 7 week non-technical trial, for which judgment has just been given.

Judgment

There’s a lot to unpack in this judgment, but here is a short list of what we think are the most important findings:

General principles:

- There is only one set of FRAND terms in a given set of circumstances. Note the contrast between this and the comments of the Hague District Court in the Netherlands in Archos v Philips (here, in Dutch) which seem to interpret the CJEU decision in Huawei v ZTE as meaning that there can be a range of FRAND rates.

- Injunctive relief is available if an implementer refuses to take a FRAND licence determined by the court. Mr Justice Birss indicated that an injunction would be granted against Huawei at a post-judgment hearing in a few weeks’ time (although presumably Huawei can avoid this by now taking a licence on the terms set by the Judge).

- UP is entitled to damages dating back to 1 January 2013 at the determined major markets FRAND rate applied to UK sales.

- What constitutes a FRAND rate does not vary depending on the size of the licensee.

- For a portfolio like UP’s and for an implementer like Huawei, a FRAND licence is worldwide.

- It’s still legitimate to make offers higher or lower than FRAND if they do not disrupt or prejudice negotiations.

Abuse of dominance:

- UP did not abuse its dominant position by issuing proceedings for an injunction prematurely (it began the litigation without complying with the Huawei v ZTE framework).

Calculating the FRAND rate:

- A FRAND royalty rate can be determined by making appropriate adjustments to a ‘benchmark rate’ primarily based upon the SEP holder’s portfolio.

- In the alternative, if a UK-only portfolio licence was appropriate, an uplift of 100% on the benchmark rates would be required.

- Counting patents is the only practical approach for assessing the value of sizeable patent portfolios, although it may be possible to identify a patent as an exceptional ‘keystone’ invention.

- Comparable, freely negotiated licences can be used as to determine a FRAND rate.

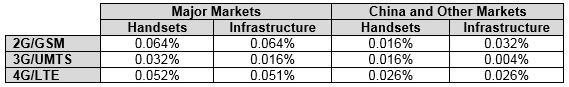

The FRAND rates as determined:

Other FRAND terms:

- The Judge goes into some details as to the terms which will be FRAND in the licence between Unwired Planet and Huawei – much of which will be worth reading for licensors and licensees in this field. Of particular note is the royalty base for infrastructure (excluding services).

Other remedies:

- Damages are compensatory and are pegged to the FRAND rate.

Comment

There have been near continual disputes between the major players in the TMT field over the last decade or so. The meaning of FRAND has been strategically important in a large number of cases. However, many of these companies are very effective negotiators. In the vast majority of cases, they are able to agree licences without resorting to litigation. Where proceedings are initiated, the parties are usually able to settle long before a judgment is reached, particularly given the time and expense required to take a FRAND case all the way to trial. (Such expense is, however, usually dwarfed by the value of the licence – many licences in this field are valued in $billions.)

The scarcity of judicial opinion in this area means this is a rare opportunity to see how a respected UK judge has approached a number of the unresolved questions regarding FRAND.

A number of significant questions remain unanswered however, and we will be exploring these in future blog posts. There’s also the matter of the upcoming post-judgment hearing in a few weeks’ time, which will establish whether or not Huawei will actually be subject to an injunction in the UK, and of course the chance that either party might wish to appeal. All in all, there’s plenty of interest to talk about, plenty of advice to be given to clients, and the FRAND debate will undoubtedly continue on.

Pat Treacy

Sophie Lawrance

Author

Edwin Bond

Author

Francion Brooks

Author

Matthew Hunt

Author